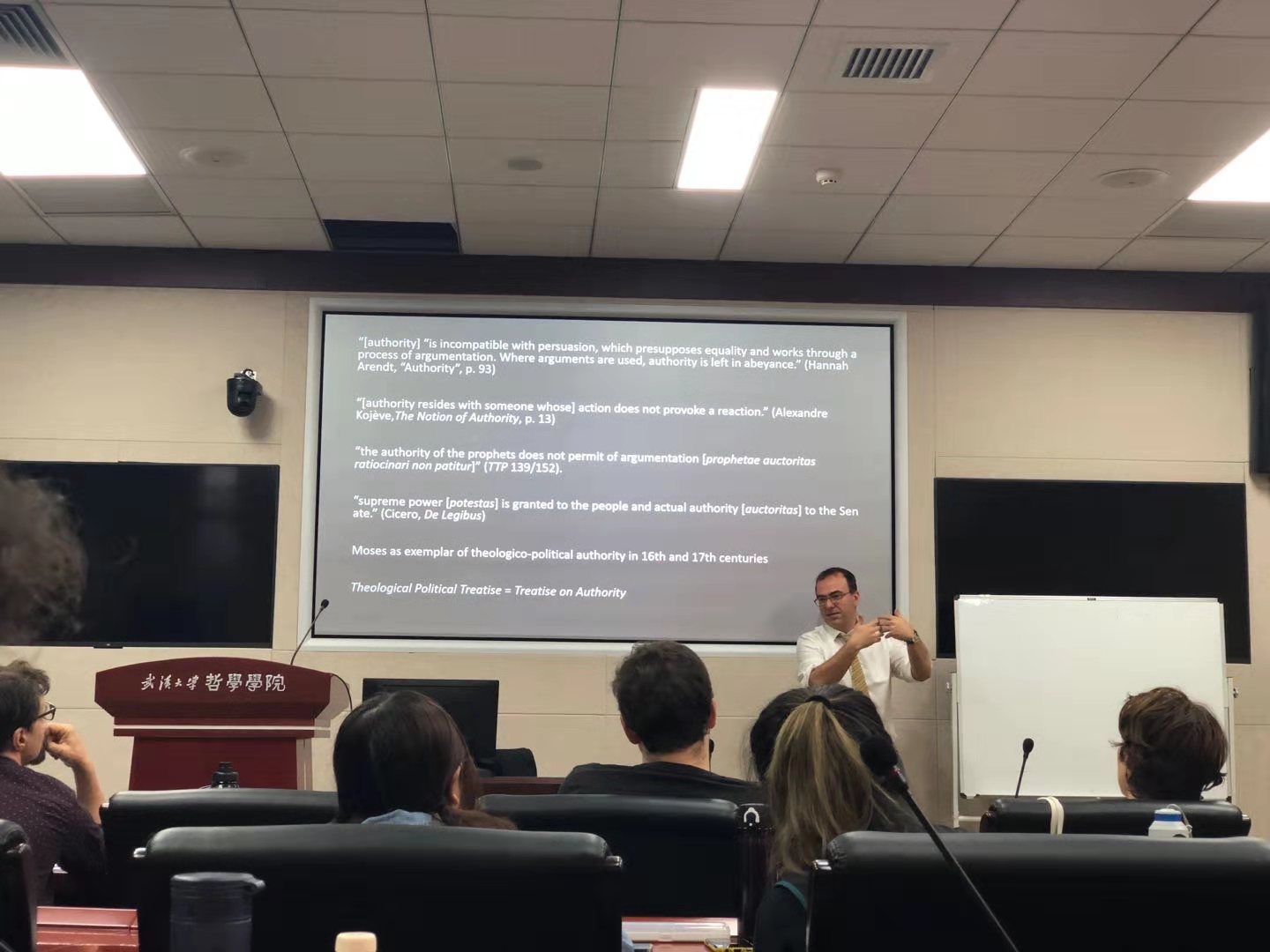

On September 26th, Dimitris Vardoulakis delivered a lecture on "What Moses Can Teach us about Donald Trump" at Room B214 in Zhenhua Building. Dimitris is from Philosophy Department of Western Sydney University.

At the beginning, Dimitris played a video of Donald Trump, in which when President Donald Trump was addressing at the UN general assembly, the delegates laughed at him. And Dimitris came to question how a leader who has political power puts himself at a position of being laughed at, and how it is possible that one is powerful but has less authority.

Then he turned to elaborate two key characteristics of authority. The first key characteristic is that authority is beyond contestation, and the figure of authority cannot be argued with. And authority cannot stand laughing, in the sense that laughing means critical judgement against authority. The second key characteristic is that authority has two origins: the theological one and the political one. Those who are obeyed because the authority itself have theological authority, while those who have authority because being obeyed have political authority. Moses is the representation of having both theological authorities derived from revelation, and political authority derived from law. That Moses is a representation of double authorities is prevalent within Jewish and Christian tradition. However, Spinoza argues that it's Moses's activity of communication and interpretation that establish his authority, which undermines the traditional double origin theory.

To highlight the radicality of Spinoza's conception of authority, Dimitris then juxtaposed it to the iconography of Moses. Three paintings are introduced. The first one is Cosimo Rosselli's Moses and the Tables of The Law, which is traditional interpretation of the theological-political origins of authority. The vertical axis of this painting depicts the theological authority placing Moses higher than everyone else, whereas the horizontal axis depicts political authority describing the path about the establishment of the Hebrew state. The second painting is Ferdinand Bol’s Moses descends from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments. The painting depicts the moments when Moses descends from Mount Sinai a second time, contrasting the distance between the most high and the most low. Moses’s authority is based on his proximity to heaven. And thus his authority is primarily theological in Bol’s painting. The third one is Rembrandt’s Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law. Rembrandt depicts the moment when Moses is about to breaking the tablet before ordering killing of those who lapsed into idolatry. The anticipation of authority over life and death shows that Moses’s authority here is primarily political.

After elaborating three kinds of iconography of Moses, Dimitris turned back to Spinoza’s answer to the origin of authority. Spinoza claims that natural knowledge is common to all and that prophecy is one species of natural knowledge. However, people mistake that prophecy is superior to natural knowledge and hence that prophet’s interpretations, like Moses’s, are beyond contestation, which merit prophet authority. Thus, the origin of authority results from mistake about superiority of revelation over natural knowledge.

Finally, Dimitris talked about inversed relation between authority and populism in Donald Trump case. A populist leader like Trump who says what people like to listen to, but what is not truth, has less authority, while a leader who has more authority is less popular. One cannot form a rational argument when arguing with someone in Trump’s position, because Trump is lying. What trump has is opposite to authority, and however leads to the same thing as authority, that is the impossibility to argue with.

After finishing his lecture, Dimitris answered to the question raised by the attending faculty members and students. And the discussion lasted for more than an hour.